The Man Without Fear...By The Year: Daredevil Comics in 1983

By Bruno Savill De Jong — It’s 1983. President Regan proposes the Strategic Defense Initiative (nicknamed the “Star Wars program”), Margaret Thatcher wins a landslide victory in the UK’s General Election and the Mario Bros. game debuted in arcades. People are listening to “Total Eclipse of the Heart,” watching Scarface and reading Daredevil.

Written by Alan Brennert (192), Larry Hama (193, breakdowns on 196), Dennis O’Neil (194-201)

Illustrated by Klaus Janson (192-196), William Johnson (197-201)

Inks by Klaus Janson (192-196), Mike Mignola (197), Danny Bulanadi (198-201)

Colors by Klaus Janson (192-193), Glynis Wein (194-195, 198), Christie Scheele (196-197, 200-201), Bob Sharen (199)

Lettered by Joe Rosen

Frank Miller eclipses most other writers on Daredevil. This is true of those that came before him, but it’s incredibly true of those that followed on from him. To the extent that Daredevil from 1983 has not been collected anywhere; not in trades or on Marvel Unlimited (hence the roughness of the scans). It’s fascinating to see that history reacts to Frank Miller’s seismic impact by undermining the sequential stories around him. Not that 1983 contains many hidden gems, as it mostly attempts to revert to serialised adventures from before Miller took over. Yet at the same time, Daredevil had been irrevocably altered by the last few years, leaving new writers to pick up the pieces.

The issue right after Miller left, “Promises” (Daredevil #192), was written by Alan Brennert but still illustrated by Klaus Janson. According to Brennert, everyone at Marvel was intimidated from following up Miller’s seminal run, so he leapt at the freelance offer from Dennis O’Neil. Brennert maintains Miller’s tone of true-crime and corruption, focusing on how Ben Urich and his wife Doris wish to move out from their disgusting New York slum apartment. Yet signing a miraculous new lease would inadvertently plant them within the pocket of the Kingpin. Urich’s moral hurdles of maintaining an honest life surrounded by corruption – including his journalistic mentor being under the thumb of the mob – nicely aligns with the elements Miller had established. Although Brennert admits he added some snappy Stan Lee banter and had Matt less psychologically damaged, retreated Daredevil into safe and familiar territory. Likewise, the layouts are less experimental and distinctive than during Miller’s tenure.

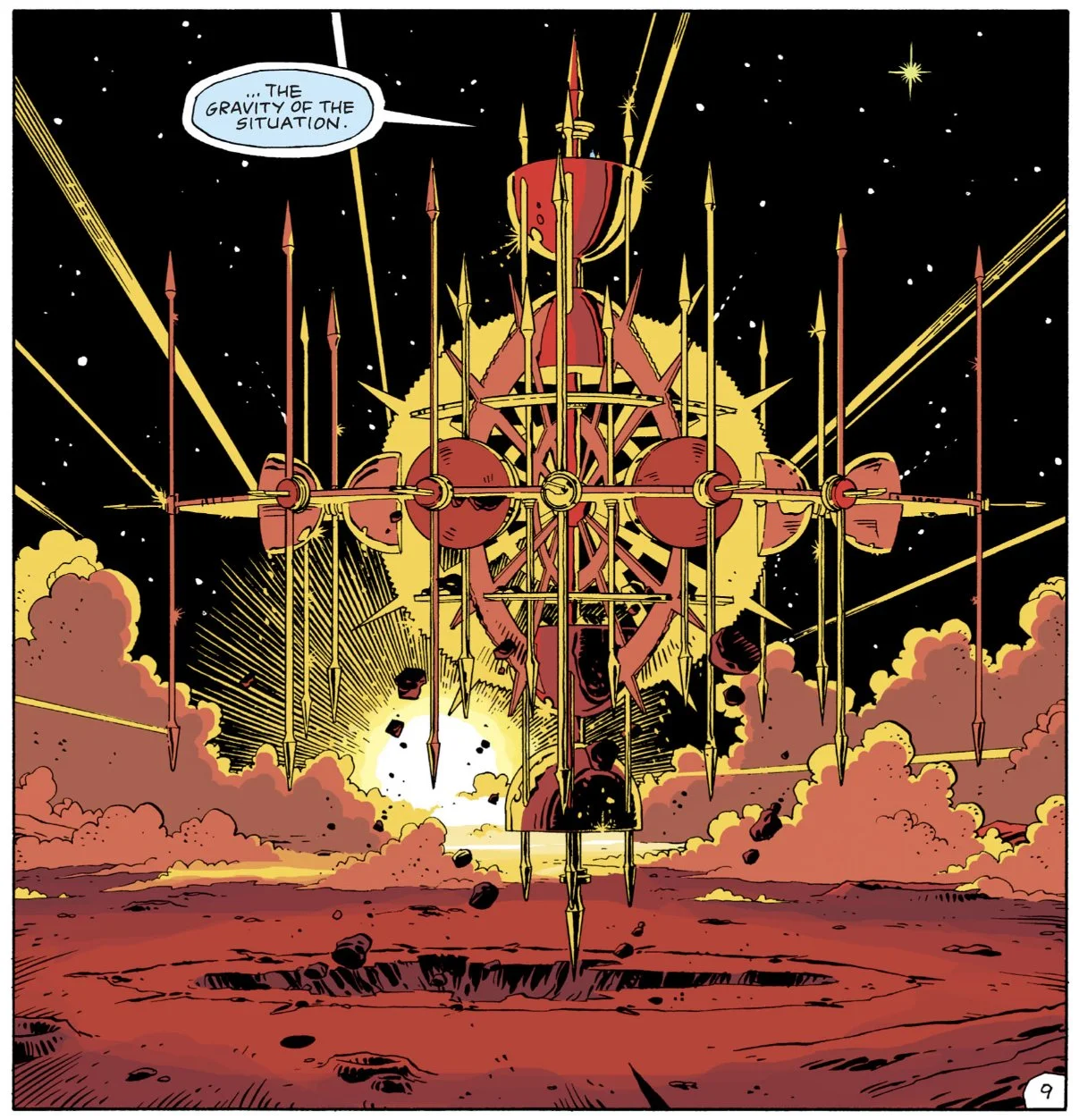

After a bizarrely inconsequential cruise-ship robbery story by Larry Hama, Dennis O’Neil – the Marvel editor who steered Frank Miller aboard Daredevil and wrote some of Daredevil #18 way back in 1966 – took over the book. O’Neil picks up the thread of Bullseye, whose body was paralysed by Daredevil, and is now transported by Japanese gangster Lord Dark Wind to be cybernetically repaired. O’Neil continues the Bullseye storyline but not quite the one, returning Daredevil to an action-heavy series with goofy visuals (like Matt wearing samurai robes over his Daredevil costume) that mostly feels perfunctory.

Daredevil’s excursion to Japan likewise feels outdated now. It is not actively offensive – aside from lines like “I’d like to know how an Oriental might smuggle an invalid out of the country” – but it plays into orientalist stereotypes of a primitive and honor-bound Japan. It reads like a colonialist adventure template which many comics of the time relied upon. Indeed, Marvel in the 1980s often mined Japan as an exotic place for stories, Frank Miller and Chris Claremont set their Wolverine limited-series within Japan, and Miller introduced the Hand ninjas and fighting styles in Daredevil, before leaving the book to write Ronin for DC Comics.

In fairness, Larry Hama – a legendary Japanese-Korean-American comic creator – is credited with involvement in these stories, and Lord Dark Wind is meant to have an intentionally backwards notion of society. He instructs his henchmen to only, and asks the recently-healed Bullseye to assassinate the Minister of Trade, disgusted that the “New Japan” is dependent on Western Capitalism and lacks traditional honour. Dark Wind is a failed kamikaze pilot from WW2, and his apparent “shame” from surviving makes him wish to return Japan to its traditional roots, attempting to recreate a past that is constantly slipping away.

In Japan, Daredevil is accompanied by (and maybe sleeps with) Lord Dark Wind’s daughter Yuriko, who will later become Lady Deathstrike. Yuriko despises her father and requests that Daredevil kill him and his henchmen. Matt, however, maintains he is “not a killer.” Much of 1983 involves Daredevil opposing such lethal force. Wolverine appears in New York to team-up with Daredevil and inform him of Lord Dark Wind’s abduction of Bullseye, and he gleefully cuts through henchmen and appears to revel in the violence much like the Punisher. Plus, Daredevil had earlier encountered a “murder squad” composed of police officers and controlled by police commissioner Turkington Brown, who were executing known criminals under their own jurisdiction.

Turkington Brown is an interesting figure. At a party, a drunken Heather Glenn lets slip to him that Matt Murdock is Daredevil. With this information, Turkington unsuccessfully sends hitmen after him, and when the two confront each other, Turkington reveals he has a terminal illness. He rants how “there’s a war and we’re losing. And the terrorists and the punks and the hoodlums are winning.” Yet Matt actually allows Turkington to get away with his actions, in exchange for keeping his identity secret.

It’s the kind of moral compromise Daredevil had opposed in “Promises,” but here it is accepted without comment. Daredevil even saves Turkington’s life after Wolverine stabs him, letting Bullseye get away to rescue his enemy who will die anyway. It feels like O’Neil is establishing a great rivalry between Matt and Turkington, with Matt continually ‘helping’ Turkington from his moral compass. Yet, when Matt returns from Japan, Foggy Nelson casually tells him how Turkington Brown died off-screen.

Yet Turkington adds to the prevailing ‘morality tales’ of 1983 Daredevil. O’Neil’s first issue has Matt hired to defend the retired renowned counterfeiter Jeremiah Jenks, who fled from a strict religious sect when younger, and now seeks atonement. Matt defends Jenks, protecting the self-confessed criminal due to his genuine repentance. Less altruistically, Matt also defends “Bruno Ponchantrane,” a crime-lord who apparently “slaughtered a little girl,” yet Matt gets him off on a technicality (why he took the case is never made clear). This is who Matt defends from Turkington’s vigilante justice. Throughout the year, Daredevil makes it clear how he reveres the law and is opposed to killing. He even admiringly recounts how a former veteran carried around a busted gun from Vietnam since, even in combat, he “couldn’t bring himself to pull the trigger.” In 1983, lethal force repeatedly comes up, only for Daredevil to firmly reject it. That is, until Bullseye comes back.

When a recovered Bullseye returns to New York – in Daredevil’s 200th issue – Daredevil has the explicit goal of killing him. Ever since Lord Dark Wind stole him away, Daredevil has chased him around the world to “finish what he started” and ensure Bullseye never harms anyone else again. Bullseye feels the same, being tasked by Kingpin to first finish off Daredevil. Indeed, their mutual hatred is so strong it seemingly forms some kind of psychic bond, each able to sense the “presence” of the other.

The two clash inside St James Arena, fighting a brutal extended battle which has venom laced into every insult. Bullseye resents Daredevil’s “mercy,” viewing his paralysis as worse than death since it signals he is not “worth” killing. When Bullseye taunts Daredevil over his murder of Elektra, Matt goes menacingly silent. In a rage, he is about to execute Bullseye, before remembering his father – who worked at the Arena as the masked wrestler Red Devil – saying “there’s never any reason for not bein’ who you are.” Faced with this choice, Matt reiterates that he is no killer, and that his torment over Bullseye was not from failing to kill him, but from trying to in the first place.

It's tough to not read Daredevil #200 as a response to the last Bullseye/Daredevil encounter (and Frank Miller’s final issue), “Roulette.” There, Matt pondered the cyclical nature of violence, weighing whether his violent crusade was justified or not – whether it was better to kill Bullseye, or himself – but leaving it an open-ended morally grey question. Daredevil #200, meanwhile, closes that loop by answering that Daredevil is “no killer,” and that even thinking otherwise was wrong.

While “Roulette” featured a retcon of Jack Murdock being an imperfect father who once hit Matt, Daredevil #200 features Jack Murdock giving vulnerable moral advice about sticking to one’s morals, re-establishing him as a sentimental patriarchal idol. Daredevil #200 is even called “Redemption,” with Daredevil ‘redeeming’ his moral ambiguity from the previous era and, in the aftermath of ethical dilemmas, reaffirming them as distinctly black and white.

Now, in real life I’m completely opposed to capital punishment, and I prefer my superheroes to be non-lethal. But 1983 can’t help but feel like backtracking from the murky anti-hero antics Frank Miller had built up. Even before this moral revelation, Daredevil generally seems healthier and more straightforward than the previous year. I’m not against Daredevil being ‘happy’ (although he hardly has much personal life in these stories), but 1983 largely feels like a regression. The same is true of the artwork, which is finely pencilled by William Johnson, but comes across like a generic “house-style” compared to the imaginative layouts under Miller and Janson. Just as Lord Dark Wind seeks to re-establish a traditional code of conduct, so is 1983’s Daredevil largely intimidated by new, modernising developments. But such seismic events cannot be ignored.

Read classic Daredevil Comics!

Check out past installments from The Man Without Fear…By The Year!

Check out Bruno Savill De Jong’s last regular series, Gotham Central Case by Case!

Bruno Savill De Jong is a recent undergraduate of English and freelance writer on films and comics, living in London. His infrequent comics-blog is Panels are Windows and semi-frequent Twitter is BrunoSavillDeJo.