The Man Without Fear...By The Year: 1973

By Bruno Savill De Jong — It’s 1973. The Paris Peace Accords end direct US involvement in Vietnam, Roe v. Wade federally legalizes abortion, and the Sydney Opera House is opened. People are listening to “Let’s Get it On,” watching The Exorcist, and reading Daredevil.

Written by Gerry Conway (95-96), Steve Gerber (97-101, 103-107), Chris Claremont (102)

Illustrated by Gene Colan (95-98, 100), Sam Kweskin (99), Rich Buckler (101), Syd Shores (102), Don Heck (103-106), Jim Starlin (105), Bob Brown (107)

Inks by Syd Shores (99), Tom Palmer (95), Ernie Chua (96-98), John Tartaglione (100), Frank Giacoia (101-102), Sal Trapani (103-104, 106), Don Perlin (105), Sal Buscema (107)

Colors by George Roussos (98, 101, 103, 106), Stan Goldberg (99-100), Artie Simek (102), Janice Cohen (105), Petra Goldberg (104, 107)

Lettered by Artie Simek (99-103), Sam Rosen, John Costanza (95-97), Shelly Leferman (98, 106), Charlotte Jetter (104, 107), June Braverman (105)

“Daredevil and the Black Widow” never quite made the most of itself. The series pushed a first-wave Marvel hero onto a different coastline, attaching a former Soviet spy who could’ve provoked questions of patriotism and female liberation. But 1973 – the second and final year of being in San Francisco/having Black Widow as co-lead – primarily continues as a pulpy sci-fi series with occasional nods to something greater. Steve Gerber takes over writing duties from Gerry Conway, and a glance at 1973’s credits show the heavy rotation of craftsmen on Daredevil, including Gene Colan concluding his regular artwork on Daredevil that he’d given since 1966. In a later interview, Gerber said Daredevil was a consistent but mid-selling book which “served as a low-risk arena in which writers could hone their craft.” Daredevil and the Black Widow was practice, basically, and instead of letting San Francisco become an experimental groundwork, this year the book is mostly a dull area.

Most disappointing is the treatment of Black Widow, who despite being co-lead with Daredevil, gets frustratingly little to do. Repeatedly, Natasha is knocked unconscious by the Man-Bull, or passes out before the Disciples of Doom, or is kidnapped by Kraven the Hunter. Conway’s depiction of Natasha was imperfect, but at least she had her own agency and a vital storyline. Now Black Widow is a supporting player, at best, who is usually off-page with Daredevil being the main focus. Christopher Claremont guest-writes Daredevil #102 and actually give Black Widow something to do against a returning (and far more maniacal) Stilt-Man, but typically her contributions are weak. Gerber gives Natasha some faux-feminist outrage when Hawkeye appears in Daredevil #99 to “reclaim” her, telling him and Matt “I go where I please – with whom I please!” But the issue is still spent with Hawkeye and Daredevil “fighting” over her, and Natasha repeatedly pushed into the background.

Likewise, San Francisco continues as a frustratingly opaque backdrop for such a vibrant community that 1973’s Daredevil and the Black Widow fails to tap into. Although there is an interesting metacommentary on Daredevil feeling opposed to his new environment. 1973 “mends” the tense relationship between him and Commissioner “Ironguts” O’Hara – bonding during Daredevil’s hospitalization – but this only links the lantern-jawed hero with the establishment. San Francisco’s countercultural citizens are opposed to the establishment, calling Daredevil a “super-pig” and sometimes imploring him to “go back East” and leave them. In the margins, 1973 seems to fight against Daredevil’s West Coast placement. Although Daredevil and the Black Widow wants to have its cake and eat it too, having Matt startle his stuffy lawyers’ luncheon by saving his favorite “Opera” is The Who’s “rock-opera” Tommy to display his hipness.

Similarly, Daredevil reaches its 100th issue and has him interviewed by (real-life) journalist and co-found of Rolling Stone magazine, Jann Wenner. The interview is hampered by Daredevil refusing to reveal much about himself, including that he’s secretly blind, which isn’t “exactly the makings of an in-depth interview.” But even if Wenner isn’t privy to them, his questions do provoke flashbacks to Daredevil’s origin and muddled identity-crisis, including straightening out how Daredevil “is” the “first Daredevil” instead of a protégé trained by Mike Murdock as originally stated. Plus, certain psychedelic hallucinations enable Daredevil’s former foes (like the Jester or Leap-Frog) to make brief cameo appearances.

Such hallucinations are courtesy of Angar the Screamer, one of the many villains artificially created to destroy Daredevil in 1973. Angar is the embodiment of countercultural dissatisfaction, an ex-hippie incensed by how the promise of ‘60s “Peace & Love” was stomped on and sold out. Although his anger finds Angar operating with the same militant tactics he supposedly opposes, backed by “the Man” to do his bidding. Even his powers of hallucinations make Angar a “living LSD factory,” which combined with his slang, fringed-clothes and headband, make Angar a snapshot of the late ‘60s fading dream. Although at least Angar is a memorable relic of the era, more than the vaguely biblical Dark Messiah or straightforward brawler Ramrod.

Angar’s LSD hallucinations also give Gene Colan the excuse to go experimental with the artwork, depicting the way reality warps and bends around Daredevil. Although, as mentioned above, 1973 is when Colan stops being Daredevil’s regular artist, with a quickfire rotation of artists taking over after the 100th issue. Such pencillers are decidedly flatter and more “retro” than Colan, lacking his dynamic close-ups or heavy use of shadow. But they aren’t bad in and of themselves, with Sam Kweskin’s shark and simple linework in Daredevil #99 being especially pleasing. It just demonstrates that the consistency of 1973’s Daredevil and the Black Widow was slightly falling apart.

We should also take a second to acknowledge the colorists. Astute readers of this column will have noticed that unlike other artistic contributors, like inkers and letterers, Daredevil’s colorists have been uncredited since the start. Coloring in the early comics industry is radically different to how it’s done today, and frankly the Marvel Unlimited issues (which I’ve been reading from) have been “recolored” in a way which barely resembles the original newsprint. Still, for whatever reason, 1973 is when Daredevil (in #98) first credits its colorists – even if Daredevil #96 hilariously leaves the credit-space blank, as if warming up to it.

Much like how most of Daredevil’s 1970’s adventures were orchestrated by “Mr Klein,” 1973 has its villains predominantly be experiments and lackeys of a shadowy “Man,” eventually revealed to be Mr Broderick of Matt Murdock’s potential new law firm. Matt felt wary of prosecuting a teenager gang, despite Broderick’s insistence, and Daredevil reveals the senior lawyer as completely corrupt and desiring to achieve what he describes as “total control” of San Francisco.

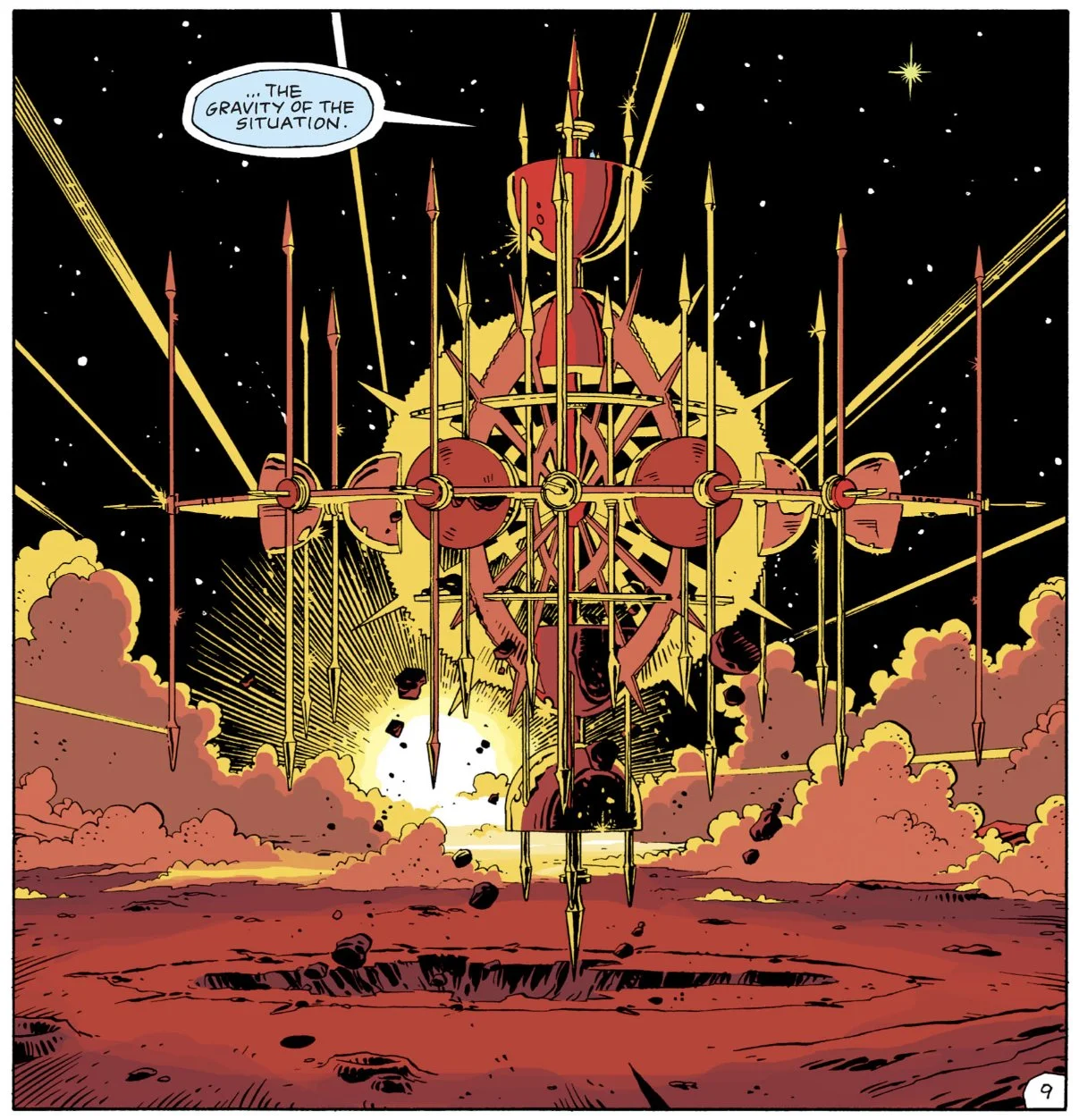

This results, quite unexpectedly, to Broderick bonding with the Terrex (creation of the Eternals) to become the “absolute monarch” of San Francisco.

Daredevil is literally plucked from thin air and taken aboard Moondragon’s ship, revealing how Broderick tricked Moondragon into thinking Daredevil was aligned with Thanos and must be destroyed. So, Daredevil gets caught up in Marvel Cosmic affairs, including the ultimate defeat of Broderick facilitated by a guest-starring Captain Marvel. Gerber is cheekier than Conway’s pulp adventures – including when Black Widow is exasperated at her broken window – but it still feels Daredevil lacks an identity of its own. Perhaps Gerber (or Marvel Editorial) felt it couldn’t be found in San Francisco, since next year has Matt return to New York and drop Black Widow from the title, but it also feels like they never truly tried.

Check out past installments from The Man Without Fear…By The Year!

Check out Bruno Savill De Jong’s last regular series, Gotham Central Case by Case!

Bruno Savill De Jong is a recent undergraduate of English and freelance writer on films and comics, living in London. His infrequent comics-blog is Panels are Windows and semi-frequent Twitter is BrunoSavillDeJo.