The Man Without Fear...By The Year: 1968

By Bruno Savill De Jong — It’s 1968. Protests against Vietnam intensify (especially following the My Lai Massacre), Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy are assassinated, The Prague Spring erupts in Czechoslovakia, and Richard Nixon is elected President of the United States. People are listening to “Sunshine of Your Love,” watching 2001: A Space Odyssey, and reading Daredevil.

Written by Stan Lee

Illustrated by Gene Colan

Inks by John Tartaglione (37, 40-41), Frank Giacoia (38), George Tuska (39), Dan Adkins (42), Vince Colletta (43-45), George Klein (46-47)

Colors unknown/unlisted

Lettered by Sam Rosen (38, 40-42), Artie Simek (37, 39, 43-47)

The year of 1968 has been called the “Year that Shattered America.” Two major assassinations — Martin Luther King Jr. and Robert Kennedy — fueled turbulent riots throughout the country. This included the 1968 Chicago Riots at the DNC against the Vietnam War, support for which had fallen to less than half the country, exacerbated by uncensored images of the Tet Offensive, the My Lai Massacre and the execution of Nguyễn Văn Lém. Media shaped – and was shaped by – the era’s changing tides, with the contemporary “New Hollywood” movement pushing mainstream films away from the safe studio system and into experimental, explicit, countercultural films like Night of the Living Dead, The Graduate, Bonnie and Clyde, and Easy Rider.

Comics’ own Bronze Age – where “social reality” crept into comics – was still a few years away, but a certain darkness can be found in the margins of 1968’s Daredevil. Daredevil #47 is most obviously touched by social relevance, which we’ll circle back to, but even Matt Murdock’s regular 1968 adventures seem tinged by the year’s turbulence.

For one thing, Daredevil is repeatedly (if unwittingly) made to act more aggressive than usual. Stan Lee usually characterized him as a confident jokester, well liked by the general public, including Vietnam G.I.’s cheering his appearance at a USO show (in Daredevil #47) and crowds trying to save him from Dr Doom (in Daredevil #37). But when Doom defeats Daredevil, he swaps bodies with him, therefore acting arrogant and authoritative when in the superhero body. Daredevil, for his part, must match Doom’s egotism in this new body, only managing to swap back with Doom after blackmailing him with having declared unilateral war against Latveria’s border countries. This high-risk gamble shows Daredevil pushed to the edge of desperation, and the fear of “Red China” commencing WW3.

Later, Daredevil is exposed to radioactive material (the same type as from his origin), which inexplicably makes him far more aggressive and challenge Captain America to a public duel. Additionally, newfound foe the Jester frames Daredevil for killing his alter-ego Jonathan Powers. This creates a police manhunt for Daredevil as he’s pursued through the city, with news cameramen commenting the public execution “will be as famous as Ruby’s shooting of Oswald!” The madness and assassinations of ‘60s televised violence is seeping its way into Daredevil.

Tragically, Daredevil also kills off his “Mike Murdock” persona, who doesn’t appear at all in 1968 – save for once with Karen in full Daredevil costume – before “dying” in a battle with the Exterminator. This mastermind recruits the Organizer’s “Ani-Men,” renames them the “Unholy Three” and creates chaos across New York. Matt seems eager to use this opportunity to drop his “triple-identity crisis,” despite not giving it much thought beforehand, and even contemplates dropping Daredevil along Mike. But the Jester’s emergence makes Matt again think of his feet, explaining there’s a “second” Daredevil that Mike was training to replace him, effectively reappearing as his own protégé. Matt fatalistically concludes, “so long as Matt Murdock lives… there will always be… a DAREDEVIL!”

This constant presence of Daredevil makes Matt, again, throw away the affections of Karen Page, who had just conveniently got over fun-loving Mike (and dashing Daredevil) and knew “it’s Matt [she] love[d]… shy, sightless, wonderful Matt!” Although the will-they-won’t-they melodrama continues, Daredevil’s Love Triangle does finally close, as Mike and Foggy are out of the way. Foggy becomes involved with Deborah Harris (also from the “Ani-Men” two-parter), with Karen and Foggy even seeming on friendly terms about their respective “partners” and setting up a double-date.

Deborah seems sincere in her relationship with Foggy, although she causes some problems with his campaign for District Attorney. Not only is Deborah an ex-con, but she regularly attends protests and outspoken activism that could compromise his profile. Unlike the submissive Karen, who usually waits around for Matt to notice her, Deborah is a relatively revolutionary woman, refusing to cower in the spotlight. It’s unclear whether Daredevil approves of this, as Matt both comments “if Washington were alive today, we’d call him a protestor” and jokes “how can you expect her to be sensible? She’s a female!” But even this old-school sexism demonstrates the rising feminism of the late ‘60s gradually affecting the series’ gender roles.

Deborah’s attitude seemingly rubs off on Karen, who makes active attempts to track Matt down during his disappearance with the Unholy Three, and when Matt coldly rebuffs her affections, Karen stands up for herself and quits Nelson & Murdock. She disappears into the city, only telling Deborah of her new position in social services. Matt regrets his actions and agonises over Karen’s departure, but it’s too little too late. Daredevil is left more despondent and alone than ever, including when he’s hunted through the city on murder charges, unable to even get home and change out of his costume in Daredevil #45’s intense, issue-long chase.

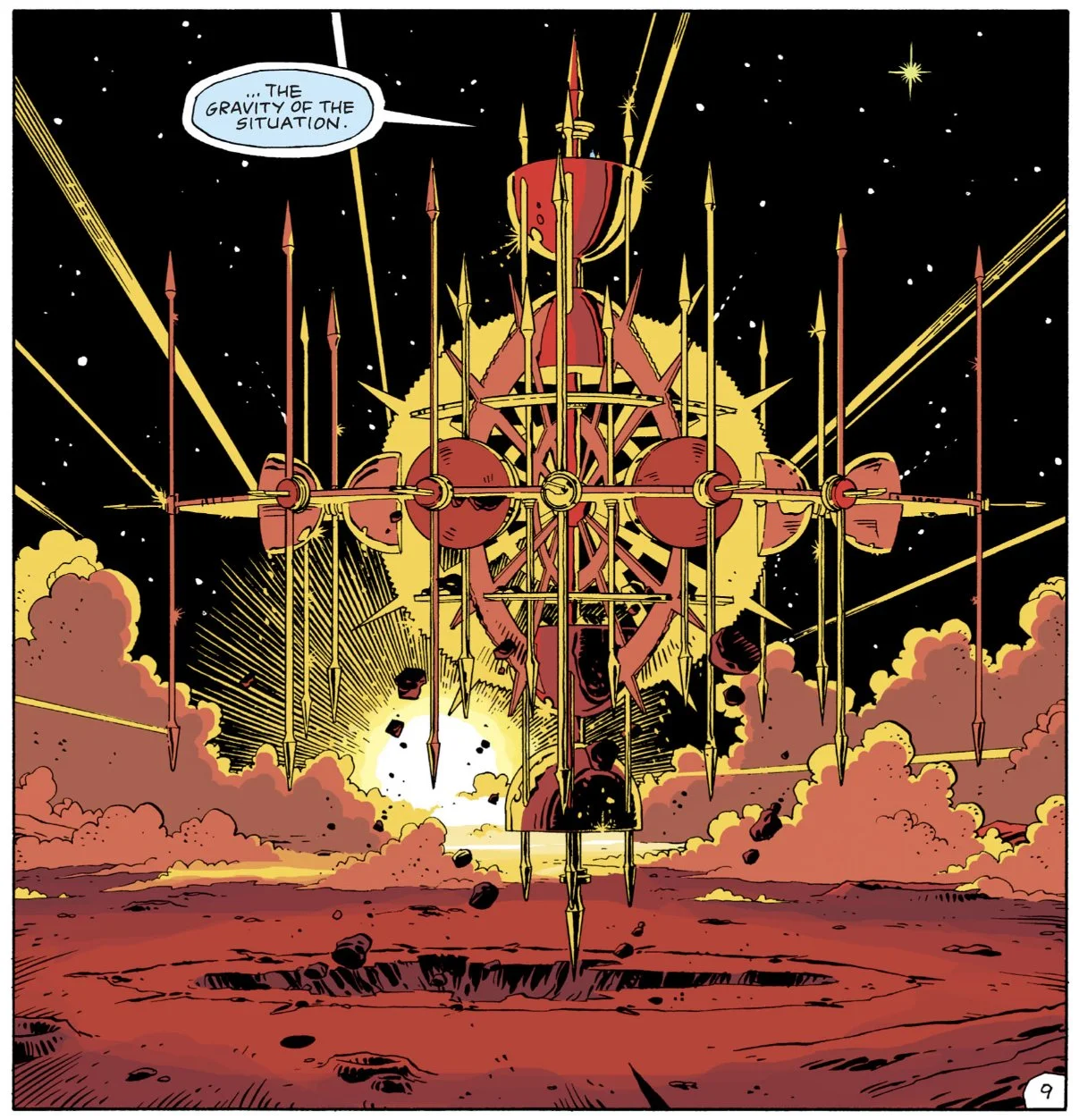

Daredevil was similarly isolated a few issues earlier, when hit by the Exterminator’s “T-Ray,” which transports its victims into a time-displaced pocket-dimension. Although the other victims Daredevil is stranded with eventually return back to reality, a malfunction with Daredevil’s delivery leaves him stranded in this strange psychedelic dimension truly and utterly alone. As Matt narrates, “time itself… which cannot be touched… which cannot be seen… is the strongest trap in all the world!” his radar-senses being futile in this intangible theoretical realm. Matt is gradually able to “pull” himself back to reality, first out of the time-displaced vortex and then from an out-of-sync stage, where Gene Colan renders Daredevil’s “normal” body against a sketchy black-and-white world.

Colan’s art generally becomes more experimental in 1968. He pushes against Marvel’s grid-paneled conventions, creating something more dynamic and impactful. From Daredevil #44 onwards, nearly all of Daredevil’s compositions are slanted and jagged, emphasizing the disorientation and momentum within their frames. Although this may not seem spectacular by today’s standards, for the time such artwork pushed against mainstream comics’ boundaries. Such layouts were a significant departure from Daredevil’s style, and signaled the frame-shattering innovation in the air.

This “revolutionary” mentality, as we’ve seen, may inform the tone of Silver Age Daredevil but not as much the content. But Daredevil #47, entitled “Brother, Take My Hand,” is different, and an issue Stan Lee singled out as a personal favorite. In it, Willie Lincoln is a Vietnam veteran who’s been blinded during combat, and must readjust back to civilian life. Instead of world-saving plots, Daredevil #47 shows Matt protecting Willie, exonerating him in court (having been framed for bribery by some gangsters) and defending his home as Daredevil. Even then, Matt uplifts the despondent sightless Willie by informing he’s also blind and that “there are lots of people – without sight – who lead useful, productive lives.”

Maybe this issue seems mawkish by today’s standards. It’s stance on war – “the most brutal – most idiotic – most loathsome of all that’s wrong with mankind! And it’s always the youngest – the finest – the best of our people that pay the highest price” – seems generalised and uncontroversial compared to later indictments of the Vietnam War. But back in 1968, any comic book opposition to Vietnam was rare. Iron Man’s 1963 origin in Vietnam condemned the “evils of Communism'' and the righteous cause of American troops. Daredevil #47 gently questions the point of the conflict, and the sacrifices young soldiers like Willie pay for it.

That the disabled, African-American Willie only “survives” re-entry to the home-front through fortunate contact from Daredevil is not critically examined. But Willie’s race (being the only African-American character in the issue, or in Daredevil at all until this point), combined with the turn towards “social relevance,” can’t help but recall the far more explicit, and famous, Green Lantern/Green Arrow #76, where a black man challenges the intergalactic Green Lantern on Civil Rights. That watershed 1970 Bronze Age moment is a few years removed from 1968’s Daredevil, and its messaging is less overt. But Matt Murdock’s surprisingly dark, turbulent and socially aware year signals the changes on the horizon, when all of America was shattered and forced to rebuild itself.

Check out past installments from The Man Without Fear…By The Year!

Check out Bruno Savill De Jong’s last regular series, Gotham Central Case by Case!

Bruno Savill De Jong is a recent undergraduate of English and freelance writer on films and comics, living in London. His infrequent comics-blog is Panels are Windows and semi-frequent Twitter is BrunoSavillDeJo.