The Man Without Fear...By The Year: Daredevil Comics in 1986, the Bill Sienkiewicz Graphic Novels

In this special edition of Bruno Savill De Jong The Man Without Fear…By The Year series, he looks at the Bill Sienkiewicz graphic novels from 1986, including Elektra: Assassin.

By Bruno Savill De Jong — It’s 1986. The Challenger Space Shuttle fatally explodes on live TV, the first case of Mad Cow Disease is recorded, MLK Day is observed as a federal holiday and the Chernobyl Nuclear Reactor undergoes a critical chain reaction. People are listening to “Livin’ On A Prayer,” watching Top Gun and reading Daredevil.

Written by Frank Miller

Illustrated by Bill Sienkiewicz

Inks by Bill Sienkiewicz

Colors by Bill Sienkiewicz

Lettered by Jim Novak

The appeal of using Daredevil for a year-by-year retrospective was how streamlined it was. Matt Murdock didn’t originate in some “Amazing Fantasy” anthology, but his own self-titled series. He’s been popular enough to be continuously running from the start, but not too popular to splinter off into other titles. From the beginning, Daredevil has been reliably providing serialised adventures through the years in a single volume. That is, until 1986.

We’ve already discussed how 1986 was a pivotal year for the comics industry. But another aspect was through its packaging. Before the 1980s, trade collections of comics were rare. But as comic speciality stores and the direct market took hold, major publishers recognized the market opening for “graphic novels,” especially after Will Eisner’s A Contract with God. The canonical works of 1986 – Watchmen, Maus, The Dark Knight Returns – would further reinforce the viability of “graphic novels,” despite all originally being released as single issues. But even before this, Marvel had recognized the growth potential, and started the Marvel Graphic Novel line in 1981. Alongside Born Again, Frank Miller returned to the Man Without Fear in 1986 with Daredevil: Love and War.

The Marvel Graphic Novel was one commercial exercise of the 1980s, but editor-in-chief Jim Shooter also experimented with the Epic Comics imprint. Epic would publish high-quality, creator-owned series which would be distributed to the direct market, and therefore avoid Comics Code Authority censorship over vulgarity and nudity. Frank Miller was commissioned to help boost sales of the imprint, resulting in the explicit and psychedelic limited-series Elektra: Assassin. So, in addition to Born Again, Frank Miller wrote two more ground-breaking, experimental, standalone Daredevil (adjacent) stories in 1986. And both were illustrated by Bill Sienkiewicz.

It’s appropriate that Sienkiewicz worked on both these books, as his distinctive art-style exemplifies the disruptive innovation occurring in ‘80s mainstream comics. Sienkiewicz strayed from traditional “representative” comic art into stylised watercolors that bordered on expressionism and abstraction. Realistic textures would press against hyper-exaggerated figures, like the enormous Kingpin within Daredevil: Love and War. Sienkiewicz’s unhinged and often lysergic artwork only emphasizes the disorienting psychological emphasis Miller foregrounds in these books.

As our own D. Emerson Eddy points out, “obsession manifests in [Love and War] in a number of ways,” as the Kingpin kidnaps a doctor’s wife to blackmail him to save Vanessa from her “living death,” reasoning he wants Dr Mondat to face the same “growing terror” in saving Vanessa as he would his own wife. Kingpin, essentially, is trying to replicate his own mental state in the Doctor. But it becomes increasingly clear that Kingpin’s affection is barely-concealed control, screaming at Vanessa to “speak” and monitoring her progress while he simultaneously snuffs out leaks in his organization with cold calculation. It builds to Vanessa confessing she seeks “escape” from Kingpin, leaving him with all the political control he could want, except for true, vulnerable, harmonious love.

Love and War carries an even darker reflection through Victor, the henchman in charge of guarding the Doctor’s wife Cheryl. Victor is also an unhinged drug-addict, who delusionally believes Cheryl to be an “angel” and a “queen” and him “her most loyal knight.” Victor is really the focus of Love and War, Sienkiewicz accompanying his increasingly unhinged mental state (including having a baboon-like face) whose inner-monologue markedly contrasts the graphic violence he causes. Victor envisions himself like a chivalrous protector, butchering his sister for talking “wrong” and tracks down Cheryl to both sleep with and kill her.

Interestingly, even Daredevil seems infected with this perverted sense of chivalry. After first rescuing Cheryl from Victor, Daredevil tells her he is her “prisoner,” and repeatedly reminds himself (exactly like Victor does) that she’s a “married woman.” Indeed, it ultimately isn’t Daredevil who rescues the captured women. He gets preoccupied with a foolhardy assault on Kingpin’s building which, it turns out, was completely pointless. Cheryl must defend herself from Victor, and Kingpin lets Vanessa leave once she’s articulated her need to go. As the men thrust themselves into positions of authority – much like Turk Barrett foolishly trying to have the upper-hand in every situation – the women take care of themselves.

It’s unclear whether this thematic result is intentional, or the consequence of a quickly truncated story. Frank Miller, after all, does not have a great track record with women, and much of Love and War does fall on infantilizing portrayals of Dr Mondat needing to re-educated the “helpless” Vanessa, and the impossibly beautiful Cheryl nearly being sexually assaulted. Yet Miller’s bombastic gender stereotypes do often feature them being undercut; Sin City has women, almost exclusively, be strippers or sex workers (or at least half-naked), but it also shows the brooding male heroes fail to protect them.

This blurred distinction carries over into Elektra: Assassin – while Love and War centers around Kingpin, Frank Miller’s other 1986 work centers on the other major supporting player of his Daredevil run. Elektra: Assassin is ever more sexually explicit than Love and War, with Elektra recalling she (might have been) molested as a girl, sadists having rape outlined on their rap sheets, and S.H.I.E.L.D. Agent Garrett complaining of his amorous overhead neighbors (thinking “My last upstairs neighbor I liked a lot better. He never made any noise until he shot himself”).

Garrett himself is an over-the-top macho parody – with an enormous upper-body and ‘70s spy moustache – whose body gets cybernetically rebuilt after a deadly encounter with Elektra, prompting his own obsession with her that carries both hate and lust. Once when Elektra is restrained, Garrett gropes her breast while holding a gun on her. As we’re told in Elektra: Assassin, “sex and violence are joined [in the limbic system], in what many regard as the birthplace of insanity.”

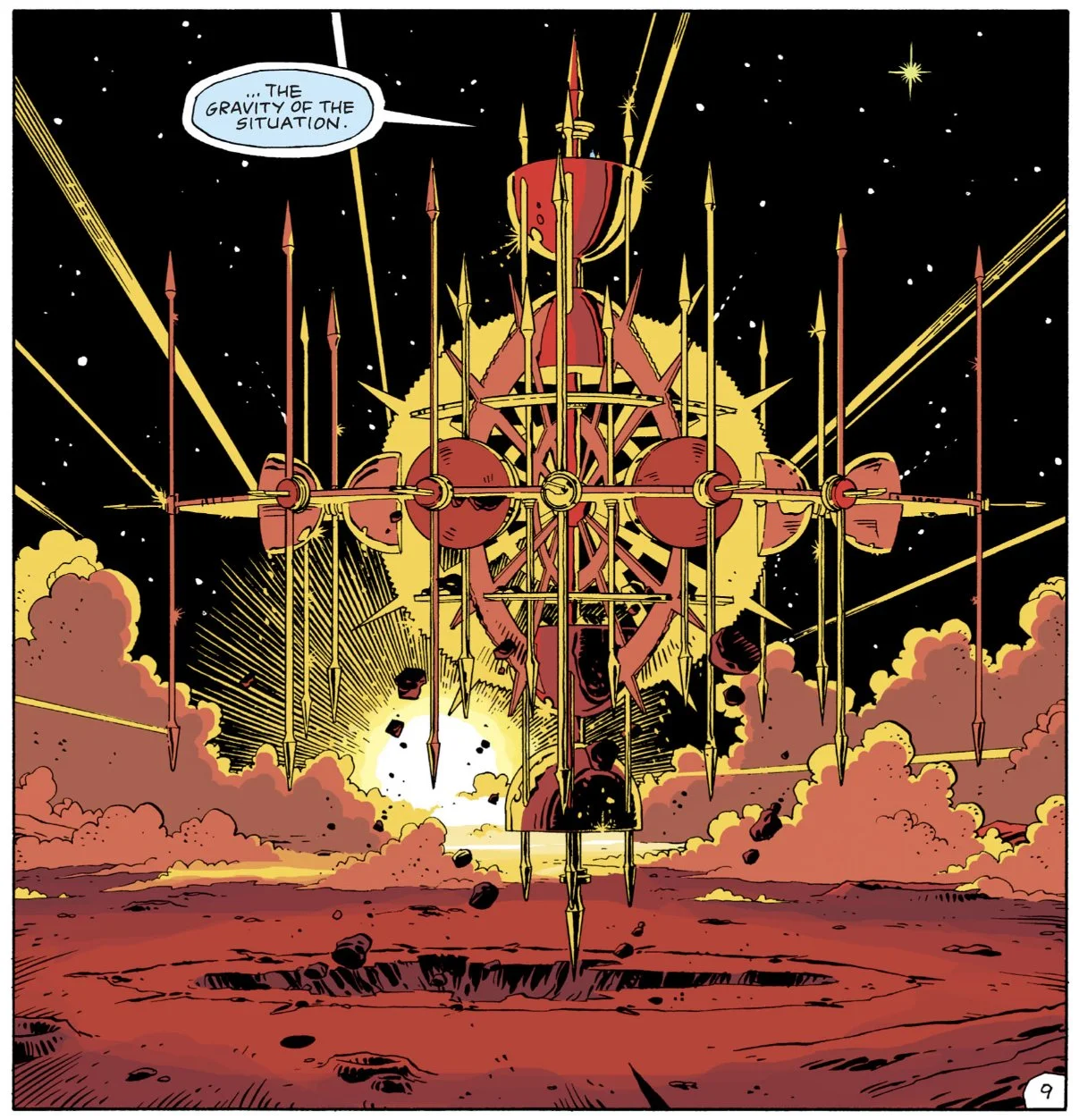

As might be clear, Elektra: Assassin is perverted, violent and unhinged in ways mainstream comics rarely were until then. Frank Miller’s other Daredevil work was fairly grounded and accessible, but Elektra: Assassin is a brazen convoluted satire which features Nick Fury sitting inside an enormous pistol, Agent Chastity McBryde infiltrates a presidential rally disguised as a nun, and Elektra tries to assassinate this presidential candidate as he’s controlled by a demonic Beast determined on starting nuclear war.

But even those plot elements are mostly background for Elektra: Assassin, a feverish ride through both Elektra and Garrett’s minds. Sometimes literally, as Elektra suddenly displays psychic powers - it is unclear and irrelevant “when” in continuity this is set – that telepathically communicates with Garrett and “throws” her mind into other’s perception. This also backfires when Elektra inhabits the mind of “Sandy,” a bubbly young girl who plays out a romantic fantasy (up until her sexual honeymoon) of a “normal life.” This traditional Reaganite white-picket lifestyle is constructed as a trap, obfuscating the “true” messy reality of Elektra: Assassin, just like how the Beast-infected presidential candidate Ken Wind is always portrayed with an unchanging grainy photograph as a face.

This is only one reading of Elektra: Assassin, which overloads the senses with information, becoming destabilised in time and plot to operate like a stream-of-consciousness story (especially in the opening issue). Even the “reality” outside the psyches has blustering caricatures of a Nixon president shouting homophobic slurs and stroking the nuclear button, while Garrett and his teammates are equally hyperviolent and constantly resurrected via outlandish cybernetic implants.

Elektra: Assassin is a difficult read whose absurdity reaches self-parody (which may be the point), but its disorienting presentation only demonstrates what an experimental time the mid-80s were for comics. This fractured, unrestrained story is the perfect vessel for Sienkiewicz’s art, every page dripping with his esoteric visuals and smeared paintings which further abstract the story. Often violent explosions and sound-effects will completely obliterate the visuals, leaving readers with a sensory-first impression before clear moment-to-moment action. This also becomes impactful whenever The Beast’s true form appears, Jim Novak’s enormous misaligned lettering adding to the horrific and demonic form.

1986 was a big year for Daredevil – and the comics industry in general – and while these graphic novels of his supporting characters are far less accessible or iconic than Born Again, they crucially represent the growing potential of comic storytelling, and the wondrous memorable depths that can be splashed on their pages.

Read classic Daredevil Comics!

Check out past installments from The Man Without Fear…By The Year!

Check out Bruno Savill De Jong’s last regular series, Gotham Central Case by Case!

Bruno Savill De Jong is a recent undergraduate of English and freelance writer on films and comics, living in London. His infrequent comics-blog is Panels are Windows and semi-frequent Twitter is BrunoSavillDeJo.